Cinema and the ‘Intense Awareness of Human Loneliness’

As Perfected in Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation

ARTICLES

3/2/20256 min read

In his book The Lonely Voice: A Study of the Short Story, Frank O’Connor writes of an ‘intense awareness of human loneliness’ that is a common occurrence within the form. The short story, he writes, always produces characters who exist ‘on the fringes of society.’ These characters belong to what he termed a ‘submerged population,’ who are either cut off or excluded from meaningful human connection and self-autonomy. This submersion renders these characters as passive entities with no control over the external factors that affect their lives.

As well as an intense awareness of loneliness, then, there is also an intense awareness of a person’s own insignificance. This awareness is not the kind of humility we experience when confronted with, say, the size of the universe. This awareness goes beyond that. It is an awareness of impotence, a general sense of helplessness when confronted with the reality of our place in society.

Changes in that society, such as socio-political shifts, mean that these submerged populations change in character ‘from generation to generation, writer to writer.’ From ‘Gogol’s officials, Turgenev’s serfs, Maupassant’s prostitutes, Chekhov’s doctors and teachers, Sherwood Anderson’s provincials,’ the submerged populations are unified by their yearning for escape. Yet, this yearning is never fulfilled. The characters remain trapped in their own circumstances, confined by their inability to change the structures around them, echoing the broader human condition where freedom feels perpetually out of reach.

In many ways, cinema at its best shares this ability to capture the ‘intense awareness of human loneliness.’ Whether it be the hero, antihero, or villain, characters in films are often in it alone, operating on those ‘fringes’ of society. Even characters as other-worldly or as powerful as a Luke Skywalker or a Darth Vader demonstrate the awareness. Time and again, no matter the genre, the setting, or the role, the protagonists and antagonists of cinema are more often than not detached outsiders, either seeking a higher meaning or working towards a specific goal.

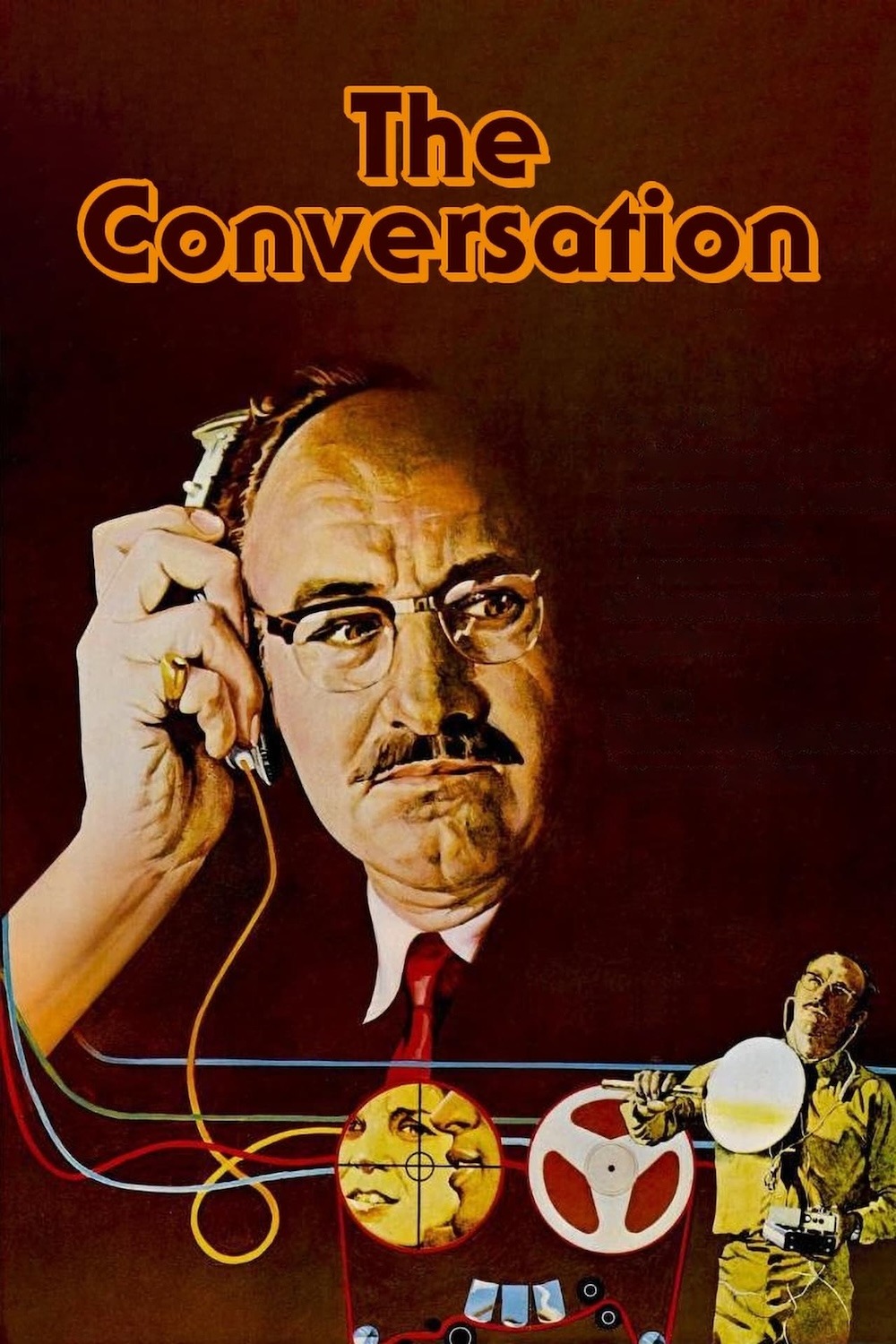

One of cinema’s great masterpieces in portraying this awareness of human loneliness is Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 film, The Conversation. The film's protagonist, Harry Caul, epitomises the intense awareness of human loneliness through his self-imposed isolation, both personally and professionally. As a surveillance expert, he is deeply entangled in the lives of others yet remains completely detached from meaningful human connection. His job requires him to observe people from a distance, which not only alienates him from them but also from himself. The very nature of his work—eavesdropping and spying—creates a sense of paranoia, amplified by a growing moral unease around the consequences of his actions. Having learned that his recordings will lead to violence or death, Harry is, essentially, retraumatised, reminded of a previous job in New York that resulted in the death of three people. Whereas in New York, however, Harry chose to flee to a place where he could continue in the profession whilst remaining emotionally uninvolved, his current job renews his ethical struggle with the knowledge of there being nowhere to run to - that these outcomes and repercussions will always be possibilities.

But The Conversation has always been more than a film about paranoia and morality, it is about privacy and responsibility. It is about those submerged, subterranean occupations, like espionage and surveillance, and an imagining of what it must be like to make a living from that line of work. But remember, it is only Harry who is undergoing this ethical dilemma, his co-workers and peers remain unbothered. His main competitor in the film, Bernie, serves as Harry’s polar opposite. As well as having great enthusiasm for surveillance, he is extremely and overtly envious of Harry’s talents. Every scene Bernie is in shows him trying to impress Harry, or making overtures towards him, seeking a collaboration. Harry’s creation then, is designed to resonate with audiences oblivious to the realm he inhabits. As Harry descends further into a state of paranoia the tables turn. The watcher becomes the watched, and we, the audience, become immersed in his terror. Yet this aspect of the film may be losing its relevance.

Watching the film today, we can see how surveillance has evolved, and the effect this has had on the importance we place on privacy. The unease of being watched or monitored has curiously lessened in the age of big data and social media, reflected in our acceptance of what Shoshana Zuboff calls surveillance capitalism - a form of capitalism that thrives on the extraction of human experience for profit, and that turns our private lives into data points to be bought, sold, and manipulated. As in the film, surveillance is now intimate, invasive, and morally ambiguous. The Conversation, and Caul’s obsession with privacy, can be seen as a reminder of how deeply privacy has been devalued in the modern world. Despite his obsession with maintaining his privacy, Caul finds himself powerless in the face of external forces determined to violate it. This struggle differs from our current reality, where the concept of privacy has become almost obsolete. In an age where our data is freely exchanged for convenience, where social media encourages us to share every aspect of our lives, and where surveillance is hard-wired into the very architecture of digital platforms, privacy is no longer a right but a commodity. The film’s portrayal of Caul's crumbling control over his life reflects our collective loss of control over our information. What was once a dystopian fear of being watched has become a daily reality, as we willingly, if unknowingly, sacrifice privacy for participation in the digital economy. The Conversation serves as a sobering reflection on how much we've lost—and how little we realize it.

But, more than anything, The Conversation remains so great as it serves not just as a masterclass in cinema, but also as an historical artifact. The film shows us how far surveillance has come, and evolved, in the decades since. Having also been released in the wake of the Watergate scandal (filming was being completed as news of the scandal broke), The Conversation serves as a living testament to the mood around the use of surveillance at that time, and how new ways of surveillance are being constantly sought. If we consider that surveillance technology was deemed out of control in the wake of Watergate, then our acquiescence to the digital surveillance of today is even more jarring.

In this sense, the film becomes a haunting one. It is a time still lingering, caught in the film’s atmosphere, music, and images, a living entity from a time once was, a relic of all that is gone. In some lost future, maybe we refuse the idea of it – the idea of mass surveillance. Or maybe we were made aware at the outset and took the necessary measures to ensure our data belongs to us only.

For Harry, existing in the time before, the battle for privacy was ultimately a battle for autonomy, a desperate attempt to maintain some semblance of control over his own life. That life is one he shares with nobody else. He occasionally sees a woman, but she knows very little about him. She doesn’t even know that it is his birthday on the occasion he visits her in the film. Curiously, he lies about his age when asked, telling her he is 42, after earlier telling his landlord he is 44. That phone call with his landlord is also telling, as he questions the landlord on how he gained access to his apartment, and how he knew it was his birthday. This ends with Harry informing the landlord that he only cares about his keys and that he should have the only set.

He is aloof with those co-workers and peers, too. Put simply, he has no interest in building relationships or maintaining existing ones, or not overtly, at least. Ultimately, like the film itself, Harry is distrustful, not just of other people but of the world itself. He is always alone, and he is aware he is alone. He is aware of human loneliness. We see this when he listens to his recordings. One such moment that stands out is when Ann reflects on a homeless man she sees asleep on a bench:

I always think that he was once somebody's baby boy. Really, I do. I think he was once somebody's baby boy, and he had a mother and a father who loved him, and now there he is, half dead on a park bench, and where are his mother or his father, all his uncle’s now?

This scene of Harry listening to these words, and the emotion we see on his face is the moment that awareness hits him. More than that, though, is a resonance, a relatability with the man on the park bench. That man could be him. Or what’s more, that man is him. Where are Harry’s parents? Where are his uncle’s now? What of any ex-lovers or children he may have?

This awareness of human loneliness, however, isn’t just in how solitary our lives are or aren’t. It is not as simple as that. Human loneliness is found in how we feel and react emotionally to circumstances and events. It is what we think about, what we keep hidden inside us. It is the knowledge of experience as being an insular one, that only we can understand our own experiences. Though people may be with us or there to help us, experiences, good and bad, ultimately remain a solitary experience in how we feel about them, how we respond to them, and the impact they have on us. Films like The Conversation, perfect this kind of loneliness.